Historical

Materialism is the application of Marxist science to historical development.

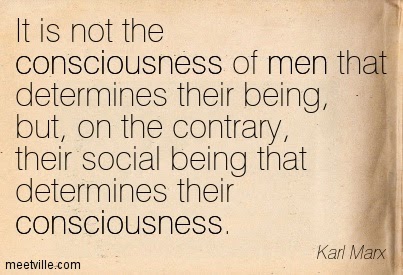

The fundamental proposition of historical materialism can be summed up in a

sentence: "it is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence,

but, on the contrary, their social existence that determines their

consciousness." (Marx, in the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of

Political Economy.)

What

does this mean? Readers of the Daily Mirror will be familiar with the

"Perishers" cartoon strip. In one incident the old dog, Wellington

wanders down to a pool full of crabs. The crabs speculate about the mysterious

divinity, the "eyeballs in the sky," which appears to them.

The

point is, that is actually how you would look at things if your universe were a

pond. Your consciousness is determined by your being. Thought is limited by the

range of experience of the species.

We

know very little about how primitive people thought, but we know what they

couldn't have been thinking about. They wouldn't have wandered about wondering

what the football results were, for instance. League football presupposes big

towns able to get crowds large enough to pay professional footballers and the

rest of the club staff. Industrial towns in their turn can only emerge when the

productivity of labour has developed to the point where a part of society can

be fed by the rest, and devote themselves to producing other requirements than

food.

In

other words, an extensive division of labour must exist. The other side of this

is that people must be accustomed to working for money and buying the things

they want from others - including tickets to the football - which, of course,

was not the case in primitive society.

So

this simple example shows how even things like professional football are

dependent on the way society makes its daily bread, on people's "social

existence".

After

all, what is mankind? The great idealist philosopher Hegel said that "man,

is a thinking being." Actually Hegel's view was a slightly more

sophisticated form of the usual religious view that man is endowed by his

Creator with a brain to admire His handiwork. It is true that thinking is one

way we are different from dung beetles, sticklebacks and lizards. But why did

humans develop the capacity to think?

Over

a hundred years ago, Engels pointed out that upright posture marked the

transition from ape to man, a completely materialist explanation. This view has

been confirmed by the more recent researches of anthropologists such as Leakey.

Upright posture liberated the hands for gripping with an opposable thumb. This

enabled tools to be used and developed.

Upright

posture also allowed early humans to rely more on the eyes, rather than the

other senses, for sensing the world around. The use of the hands developed the

powers of the brain through the medium of the eyes.

Engels

was a dialectical materialist. In no way did he minimise the importance of

thought - rather he explained how it arose. We can also see that Benjamin

Franklin, the eighteenth-century US politician and inventor, was much nearer a

materialist approach than Hegel when he defined man as a "tool-making

animal."

Darwin

showed a hundred years ago that there is a struggle for existence, and species

survive through natural selection. At first sight early humans didn't have a

lot going for them, compared with the speed of the cheetah, the strength of the

lion, or the sheer intimidating bulk of the elephant. Yet humans came to

dominate the planet and, more recently, to drive many of these more fearsome

animals to the point of extinction.

What

differentiates humanity from the lower animals is that, however self-reliant

animals such as lions may seem, they ultimately just take external nature

around them for granted, whereas, mankind progressively masters nature.

The

process whereby mankind masters nature is labour. At Marx's grave, Engels

stated that his friend's great discovery was that "mankind must first of

all eat, drink, have shelter and clothing, and therefore work before it can

pursue politics, science, art, religion etc."

While

we can't read the minds of our primitive human ancestors, we can make a pretty

good guess about what they were thinking most of the time - food. The struggle

against want has dominated history ever since.

Marxists

are often accused of being 'economic determinists'. Actually, Marxists are far

from denying the importance of ideas or the active role of individuals in

history. But precisely because we are active, we understand the limits of

individual activity, and the fact that the appropriate social conditions must

exist before our ideas and our activity can be effective.

Our

academic opponents are generally passive cynics who exalt individual activity

amid the port and walnuts from over-stuffed armchairs. We understand, with Marx

that people "make their own history...but under circumstances directly

encountered, given and transmitted from the past". We need to understand

how society is developing in order to intervene in the process. That is what we

mean when we say Marxism is the science of perspectives.

We

have seen that labour distinguishes mankind from the other animals - that

mankind progressively changes nature through labour, and in doing so changes

itself. It follows that there is a real measure of progress through all the

miseries and pitfalls of human history - the increasing ability of men and

women to master nature and subjugate it to their own requirements: in other

words, the increasing productivity of labour.

To

each stage in the development of the productive forces corresponds a certain

set of production relations. Production relation means the way people organise

themselves to gain their daily bread. Production relations are thus the

skeleton of every form of society. They provide the conditions of social

existence that determine human consciousness.

Marx

explained how the development of the productive forces brings into existence

different production relations, and different forms of class society.

By

a 'class' we mean a group of people in society with the same relationship to

the means of production. The class which owns and controls the means of

production rules society. This, at the same time, enables it to force the

oppressed or labouring class to toil in the rulers' interests. The labouring

class is forced to produce a surplus which the ruling class lives off.

Marx

explained:

"The

specific economic form in which unpaid surplus-labour is pumped out of the

direct producers determines the relationship of rulers and ruled, as it grows

directly out of production itself and, in turn, reacts upon it as a determining

element. Upon this, however, is founded the entire formation of the economic

community which grows up out of the production relations themselves; thereby

simultaneously its specific political form. It is always the direct

relationship of the owners of the conditions of production to the direct

producers-a relation always naturally corresponding to a definite stage in the

development of the methods of labour and thereby its social productivity-which

reveals the innermost secret, the hidden basis of the entire social structure,

and with it the political form of the relation of sovereignty and dependence,

in short the corresponding specific form of the state." (Capital, Vol. III.)

No comments:

Post a Comment